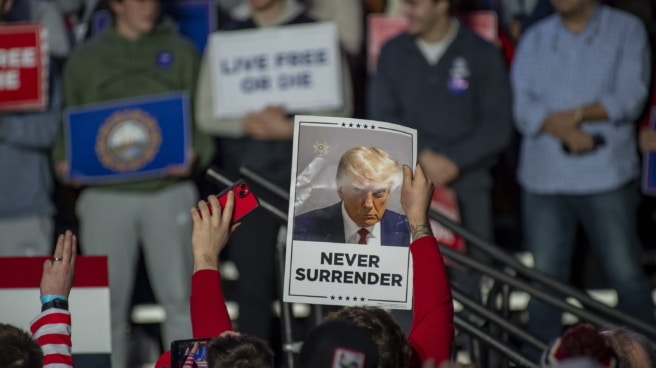

Trump supporters at the former president’s rally at the University of New Hampshire

Donald Trump’s unstoppable march toward the White House in the polls is being overcome by legal obstacles arising from his trials, although they are not insurmountable, although they do attract attention. His case is so unusual that there are no precedents to cling to, and the Constitution is limited to the statement that the candidate must be over 35 years of age and be a US citizen with 14 years of residence in the country. Trump faces four different criminal charges, with his first trial scheduled for March 4. This is a trial for trying to overturn the 2020 presidential election, which he lost to Democrat Joe Biden, whom he looks set to face again in November 2024. It’s just before Super Tuesday, a key date in the primaries that elect each party’s nominee for president.

This Wednesday, the former President suffered a setback due to the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision to disqualify him from holding public office and, as a result, from being a candidate in this state for his participation in the “insurrection” on January 6, 2021. US elections are actually 50 elections, as many as there are states. He could not appear in Colorado in the primaries, and the Republican candidate there would not be the former president, but in other states. The fact is that there are still several trials ahead. The Supreme Court will have to make a decision. The key point is how the third section of the 14th Amendment is interpreted.

What does the 14th Amendment, Section Three say?

Between 1865 and 1870, three constitutional amendments were approved to protect freed slaves and guarantee freedoms won in the Civil War. The Fourteenth Amendment covers equal protection and other rights. The purpose of the third section, dealing with disqualification from holding public office, was to prevent the Confederate rebels from governing the country which they were trying to divide into two parts. The third part of the Fourteenth Amendment, passed in 1868, states:

“No man shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elect a President or Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, in the United States or in any State, who, having first taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of the legislature of any state, or as an executive or judicial officer of any state supporting the Constitution of the United States, participated in or assisted in an insurrection or rebellion against the same or support for your enemies. But Congress may, by a two-thirds vote of each House, overturn such disqualification.” That is, an amnesty from Congress will be required.

What happened in Colorado

The lawsuit against Trump alleges that he incited and participated in the insurrection, alluding to the storming of the Capitol, and for this reason could not be a candidate for the White House. A district judge in Denver realized that there was insufficient cause to prevent him from running because he interpreted the text as not referring to presidents, although he admitted that he had participated in rebellion against the United States. The verdict was appealed, and on November 19, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled by a vote of four to three that the amendment affected the President in his capacity:Officer“(an official or government position) of the United States, and who has clearly rebelled against the State. It is curious that he is not tried for rebellion. Trump will force the Supreme Court to make a decision, and in the case of Colorado, he must respond by Dec. 4, the deadline to register as a candidate in that state.

How is the disqualification amendment interpreted?

As noted Economist, the so-called disqualification amendment is experiencing something of a renaissance. There is recent precedent: A year ago, Qui Griffin, then a New Mexico county commissioner, was removed from office by a state judge for his role in the storming of the Capitol. In August, two conservative legal scholars, Will Bode of the University of Chicago and Michael Stokes Paulsen of the University of St. Thomas in Minneapolis, argued that the 14th Amendment, Section 3, “disqualifies” Trump “and potentially many others.” having played a role in the “attempt to overthrow the 2020 presidential election.” J. Michael Luttig, a judge appointed by George H. W. Bush, and Lawrence Tribe, a Harvard law professor, agree. But other scholars on the left and right question whether Trump’s contributions to the Jan. 6 riot automatically disqualify him from office.

What will happen now?

The federal Supreme Court must decide the case first. He will probably do so, and then they will have to argue for his disqualification under the third part of the fourteenth amendment. The Supreme Court has nine justices, six of them conservative, and three of them appointed directly by Donald Trump. They are Neil M. Gorsuch, Brett M. Kavanaugh and Amy K. Barrett.

“Everyone is hoping that they will accept the appeal and come up with some more or less creative legal argument that will keep the former president on the ballot. The Fourteenth Amendment is not ambiguous: in case of insurrection, he will not be able to gain access to any office, without history or exception, the Supreme Court will have to create a very peculiar doctrine of who is a “public office”, or find some exotic pirouette (demand a final verdict) to agree with Trump,” says Roger Senserrich in his newsletter “Four Freedoms.” Senserrich adds that “the likelihood that this Supreme Court will decide to become a legend and kill Trump is minuscule, but it is not zero.”

Will the Colorado case set a precedent?

As noted New York Times, will depend on what happens in the Federal Supreme Court. At least 16 other states currently have lawsuits pending against Trump’s right to office under the 14th Amendment, according to a database maintained by national security specialist Lawfare. Four of those lawsuits—in Michigan, Oregon, New Jersey and Wisconsin—were filed in state courts. Eleven of them – in Alaska, Arizona, Nevada, New York, New Mexico, South Carolina, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia and Wyoming – are subject to federal district courts. Cases from two of those states, Arizona and Michigan, were initially dismissed by lower courts but were appealed. Another appeal was filed in Maine.

Is this legal battle hurting or benefiting Trump?

Until now, Trump has been able to present himself as the victim of a political conspiracy in order not to lose either electoral support or donors. A Reuters/Ipsos poll taken in early December shows that 52% of Republican voters would vote for the former president even if he were convicted in one of his trials, and 46% would do so even if he had to go to jail. to jail. In Senserrich’s opinion, “nothing short of a Supreme Court disqualification or an incredibly harsh ruling is going to change the campaign very much.”

Source: El Independiente