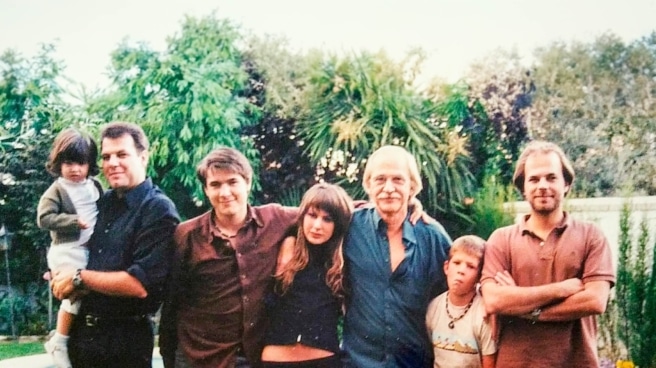

Antonio Escojotado with children.

Antonio Escojotado (1941-2021) became famous as the philosopher who opened the Amnesia nightclub in Ibiza, and also for being imprisoned after being accused of being a leader hippie mafia and for his essay General drug history, which he wrote behind bars and which has more than forty editions. And also for “stealing” the wife of one of his close friends, Sanchez Drago, and for his exile in Ibiza when he knew death was approaching. But he was much more than just a beginner. He lived freely, so much so that he did not care too much about other people’s conscience and was always guided by his own. He divided ideology into freedom and authoritarianism and sought his way of existing in the world in the former. He wrote and studied until he was exhausted and left behind books as important as Enemies of trade And Chaos and order; in addition to translating Isaac Newton and Thomas Hobbes, among others, into Spanish.

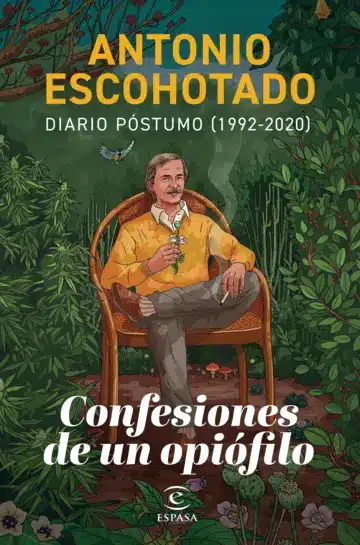

Now, thanks to his son Jorge, who has promoted his father’s legacy along with his brothers over the years, it is seeing the light of day. Confessions of an opiumophile (Espaza), a posthumous diary that Escojotado kept by hand from 1992 to 2020, which he never reread or edited, and which he forbade publication until his death. This shows another side of the lawyer, philosopher and sociologist; Your aspirations, your desires and your fears appear. Death appears as fear and purpose, nature as essence, and family as memory and refuge. And also faith not in God, but in the will that grew in him in the last years of his life.

This is almost three decades of reflection, although not daily and much less constant over time. There are years of many recordings and decades when he writes almost nothing. “This is a mysterious, hidden book that will see the light of the public only after his death and around which, precisely because of its mysterious nature, a whole legend is woven,” writes Juan Carlos Uso in the prologue, recalling the literal phrase his teacher passed on to him. “This will be published when I die, because otherwise I am sure that the gray mob will come and burn my house,” he assured him in these 238 notes, “focused on old age, physical decline and death, which are increasingly felt ” ” “next.” And above all, his advocacy of opioid use among older adults was something he knew would resonate even more than many of the politically incorrect statements he had made in life.

Because, as his son Jorge explains, here the philosopher is justifying the use of opioids such as heroin, buprenorphine patches, fentanyl, oxycodone and, above all, opium, when you are old enough and drugs do not interfere with your life project. . “What he was afraid of was public recognition and public recommendation of it. He knew they were addictive, but he also knew that at 75 it wasn’t a problem. Age takes “About ten a day? Well, I only do it a little, even if it’s illegal,” he recalls, adding that Escojotado decided to “live his old age with euphoria.” “And of course he didn’t do it with morphine, which is crap and doesn’t make you feel good. Euphoria is the joy of life, my 78 year old father, when he was in his hut in Ibiza. , told me: “Will it be today? The happiest day of my life or will it be tomorrow?

Besides, this newspaper doesn’t just talk about drugs and old age; He does it out of love, family and desire. “This is an exercise in brutal honesty. So clear, so direct… My father never said so much in four lines. First I read it in a notebook, then when we transferred it to Word, and now again when they published This is a reading of purified tablets of knowledge,” he explains about how, together with his brother Antonio, the son of his father’s second wife, they spent a whole weekend transcribing his notes. “There were times when we had to reduce the intensity,” he admits.

A family team they weren’t used to. “We all get along well, but at the end of the day, our strongest relationships are with our paternal and maternal brothers. My father had three wives and separated from my mother before I was born, so it’s difficult,” he says, adding that over the years things have been more distant between them. “I haven’t seen him much. I remember when I started reading, I saw that it was in a magazine. First line, I couldn’t read very well, but there was a photograph of him. I took it to school to show off my father and showed it to the teacher, when he saw it he said to me: “Is your father in prison?” It was in the article, but I didn’t read it. That’s how I found out that he was in prison,” he says in a conversation with this newspaper.

And it was at the age of 16 that a union took place that allowed him to now be its editor and try to make his legacy as broad and international as possible. “At that age, I moved to live with him and didn’t want to leave again. I found my father, he gave me a lot of readings, in the end we became very similar. Together we did Escota tour during which he gave 60 lectures over two years. I always say that I know my father by heart, but not because I tried very hard, but because I just listened to all his conversations,” he continues.

“To people he was a green dog because of the drug problem, because of the change in his views, because of the way he saw sex or freedom…”

“In my book Sixty weeks in the tropics He says that I am his “helper in old age and friend of the soul.” I have not parted with him for the last 15 years and was his secretary, his community manager, his literary agent…” he says. And when you ask him what it’s like to have such a unique man as Antonio Escojotado as a father, he admits that it was not easy. “Being his son is an absolute pressure , he was a wise man, his height cannot be reached. I don’t wish this on anyone. To people he was a green dog because of the drug problem, because of the change in his views, because of the way he saw sex or freedom… He had very special opinions and now his children need to prove that he is not was a green dog, but his theories are transferable, that you can take drugs without being in a ditch, change your mind without being humiliated, and we want to be able to translate that because, believe it or not, it’s even not in English,” he explains.

When asked how he feels about drugs and what he thinks about his father’s thoughts, he responds that he had “a pretty special teacher.” “He defended the sober drinking that the Romans talked about, the whole topic of opiates in old age comes from his time in Thailand because older people use them a lot. He wasn’t talking about losing his temper, but about taking a fair dose. He said that in order to not have problems with any drug, you need to take them all. He said that polydrug addiction and variety are better than drug addiction. Also about conscious self-medication, about not depending on the drug, because this is when you become dependent. That is, one orfidal is better to sleep than four drinks, and you have to know what you need and how you need it,” he continues.

And he admits that what caught his attention was the way he faced old age and death. “I won’t tell you that in the last few years he became religious, but he was a believer, he believed in a higher will and he began to talk about what happened next. His death was a lesson for me, he died with stoicism, elegance, calm. “Amazing spirit,” he recalls. And we find his entry dated May 4, 1995, where he wrote: “Is dying closer to sleep than to dreaming? Sleep is eternal, dreams are temporary” and another phrase that he said to Ricardo F. Colmenero: “First of all, I’m going to find Roman. The son I lost. And in the delirium of my imagination I say: maybe Roman will appear.”

Also the epitaph he considered on March 29, 2008, appropriate for his grave: “He wanted to be a warrior of freedom and a jeweler of language” so as not to suffer from such severe depression. The exceptional marijuana and hashish, contributed largely by the agronomists of Pamplona and Malaga, help him a lot to remain vigilant.” After all, his gravestone says, “He wanted to be brave and learned to learn.”

Source: El Independiente