Oxford University: British Prime Minister’s Factory

Of the seventeen Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom since 1940, thirteen studied at Oxford. This is a good fact for promoting this British university, especially when you know that of the four that didn’t, one lived in Edinburgh and the rest chose not to pursue a degree. The recent history of the United Kingdom can be told with this prestigious center as its protagonist, and that is exactly what one of its former students has done.

“The yellowing pages of university newspapers from the Eighties depict the same faces who monopolize British news programs today.”

SIMON COOPER

Simon Cooper (Uganda, 1969), journalist and writer, publishes Amigocracy (Captain Swing), an essay in which he analyzes the university and recounts “how a small breed of Oxford Tories took over the country.” “Teaching there is of great importance, as evidenced by the fact that one can tell the story of British politicians of the last twenty-five years with virtually no reference to any other university,” he writes in the introduction.

According to a magazine columnist Financial Times“In the yellowing pages of university newspapers in the Eighties are the same faces who monopolize British news today. Boris Johnson, Michael Gove, David Cameron, George Osborne, Theresa May, Dominic Cummings, Daniel Hunn or Jacob Ress-Mogg They argued with each other in lessons, faced each other in student elections, went to the same dances and formal dinners. They are not just colleagues: they are comrades, rivals, friends. And when they left the world of student debate for the national stage, they brought university politics with them.

Lazy, harassers and racists

It may seem that Oxford, as most people think, is a machine of bright and successful students. But Cooper, who went to Oxford to study history and German in the late Eighties, when David Cameron, Boris Johnson, Michael Gove and Jeremy Hunt had just graduated, and who was not a graduate high school (a private school in the United Kingdom), like most students, portrays the university as “sleazy, full of lazy people, a center of sexual harassment and racism”, where expectations were zero, social class was important and where the only thing that mattered was ability to speak in public . Moreover, he admits that, to his “dismay”, he sees himself reflected in the Oxford Tories: “I also learned to make a living by writing and speaking unknowingly.”

Social classes on campus have become more acute, Cooper said. Depending on your career and the effort you put into it, they knew whether you had a good or bad background. “Within the Oxbridge chivalric tradition [neologismo para designar a las universidades de Oxford y Cambridge]“The more useless the degree was, the more elegant it was,” he says, before talking about the most exclusive club at one of the world’s most exclusive universities.

Bullingdon “Package”

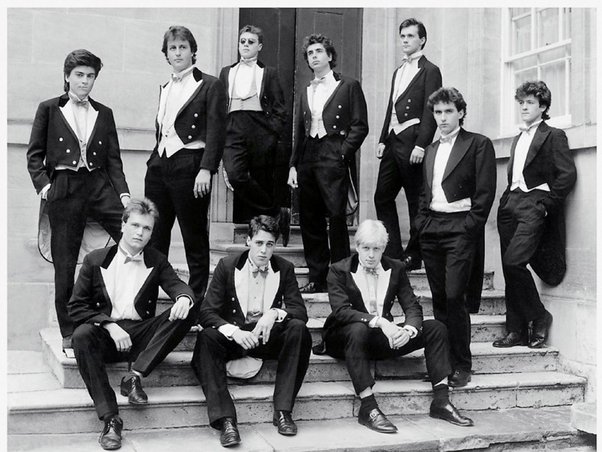

“The most famous photograph of Oxford from the 1980s, probably taken in 1987, is a group portrait of David Cameron, Boris Johnson and eight other young men on the courtyard steps of Christ Church College, dressed in Oxford suits. Bullingdon Club blue bow tie and mustard waistcoat. According to commentator Toby Young: Uniform of the ruling classCooper adds that it was a transgressive club “only in its virulently anti-meritocratic character: almost all its members were selected on the basis of their social background and gender. “They were known for their exhibitionism and entitlement.”

These were noble hooligans. “Its members moved in packs, destroying restaurants or the rooms of new members, popping bottles in the streets, humiliating sex workers hired for the occasion, or pulling down men’s pants.” strangers lower caste. And if that wasn’t enough, they humiliated their victims even more. commoners with economic compensation. Message? “The rules don’t apply to our class.” After all, it was the members of Bullingdon who were going to dictate the laws in the future.” And so it was. Although some of its members are now ashamed of this photo (Cameron and Johnson have apologized many times for their attitude towards membership), the creation of this club was a common feature of many subsequent British leaders, including the Oxford Union.

“If Johnson, Gove, Hanan, Dominic, Cummings and Rees-Mogg had not been accepted into Oxford at the age of seventeen, Brexit would never have happened.”

SIMON COOPER

“The Union was one of the reasons why students were interested in politics, especially the Tories, who came from high school, they chose Oxford over Cambridge and explains why Oxford specializes in training prime ministers. From its inception, the debating society functioned as a community nursery, dominated by Etonians (from the private Eton School),” he explains of this private society that everyone wanted to join and where politicians of Churchill’s stature came to listen to the young Prominent members of it society was Boris Johnson, who realized, according to Cooper, the great British dream: go to Oxford, find a woman at the university, get married and become President of the Union.

Humanists… and Eurosceptics

A society in which the Euroscepticism of some Oxford students can be said to have originated. It was Patrick Robertson, a Scot who grew up between Paris and Rome, one of the first students to openly oppose his country’s membership of Europe and who turned to Thatcher after she, having supported the creation of the EU, opposed the common currency and the “aggressive force” of Brussels . Despite the best efforts of Robertson, who used the Union as a mouthpiece and blindsided the Prime Minister, “Euroscepticism at Oxford was little more than a fringe movement” until the 1990s, after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the “new revival” “continent”, these ideas gained considerable strength among the university elite. So much so that, according to Cooper, “if Johnson, Gove, Hanan, Dominic, Cummings and Rees-Mogg had not been accepted into Oxford at the age of seventeen, Brexit would never have happened.”

Many of the Leave MPs who came from Oxford had one thing in common: they had studied classical literature or history, a pattern that Cooper analyzes in one chapter of his essay. “The most pro-Brexit degree among MPs in 2016 was classics, with six of the eight classics in the House of Commons voting to leave the EU. At the time, if you were in the right class, classics was the most common degree,” Cooper says. The second was a history course, “more like British history. They based the story on the narrative of Britain’s past. The structure itself was high politics, and at the center of this global vision, which stretched from Madras to Melbourne, was Westminster.”

So the author concludes that the majority of those who voted yes had studied courses that spoke of the past, of the best years of a more authentic, stronger and more prosperous United Kingdom, and that they belonged to those families that they contributed to into the history of the country. And he quotes Ivan Rogers, who studied history at Oxford and who was the United Kingdom’s permanent representative to the European Union until his resignation in 2017, and who saw Brexit “as a revolution of the British ruling class: without plan or planning.” A bunch of nonsense with that over-confidence in their own abilities that makes them think they know the true interests of others better than they do themselves.”

Source: El Independiente