A woman looks at one of the works at the exhibition “Picasso 1906. The Great Transformation” at the Reina Sofia Museum.

This year, almost 40 exhibitions about Picasso were presented. The celebration of his death filled museums and galleries with various interpretations and different artistic stages of the Malaga artist’s work, and now the Reina Sofia Museum wants to complete the cycle with one of the most striking works. WITH Ladies of Avignon (1907), as an end rather than a beginning, presents an exhibition where the protagonist is a naked man, and many of the characters in his paintings are genderless. They talk about “homoeroticism,” “otherness,” and the perception of the nude as a “symbol of acceptance” in works created by the artist shortly before “this modernist milestone.”

They do it with an exhibition, Picasso 1906. The Great Metamorphosis, in which they focus on the year leading up to this “final explosion, and which was an artistically significant moment when the experiments of the man from Malaga opened his work to other languages.” The exhibition is curated by Eugenio Carmona, professor of art history at the University of Malaga, member of the Queen’s Board of Trustees, and specialist in Spanish artists; which guarantees that Picasso’s artistic activity at that time took place in three important places: Paris, Gossol and Paris again; where he changed his understanding of nudity and sharpened his sense of transculturalism. “The year 1906 was a complete process for him. This is a strange, unique and peculiar year for him; it was the year when he made a radical turn in his work, as well as in his life, leaving behind melancholic symbolism and bohemianism,” he explains.

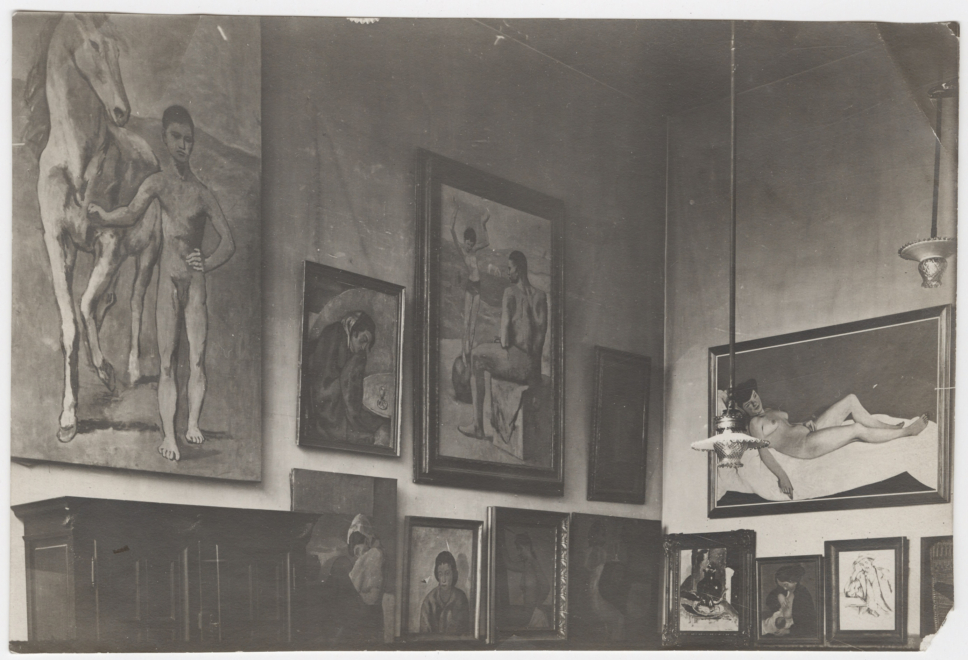

Photos of the halls of the Picasso exhibition at the Reina Sofia National Museum.

And to tell the public about this, he selected 120 works in which loans from major museums play a fundamental role and in which Gertrude Stein appears as the main character of this artistic transformation. As Manuel Segade, the institution’s director, explains, it features works “from the MoMa, the Metropolitan, various Picasso museums in Spain and Paris, the Louvre, the Pompidou, the Prado and even the Archaeological Museum.” that this rereading they have undertaken is very important because it has “immense educational value for young people who will be able to connect with Picasso’s story like never before.”

With Picasso and with those who accompanied him, because, as already mentioned, almost the partner of the exhibition is the American Gertrude Stein. “Their relationship is decisive, without them he would not have been Picasso, it was a very deep friendship,” says Carmona and recalls that the painting Nude, hands together what was in Stein’s possession was the only one who never wanted to separate, “he did not part with this work all his life.” Thus, she appeared at the exhibition because it gave her “the opportunity to interact with important contemporary creators, as well as dealers and collectors. This played a decisive role in her own definition as an artist, which was also influenced by her interest in homoerotic or ethnological photography. and reproductions in popular magazines and in libertarian and anarchist thought.

Because another of the main themes of this exhibition is the body and how it was represented, especially in the case of men. “How sad it is to say that Picasso was not interested in Stein because she was fat and a lesbian! If already in 1904 he painted his first nude lesbian couples. I can’t stand that there is not a single text about Picasso that contains any hints of his homophobia and misogyny. It seems that when you put yourself in a different position, you adhere to fashion, but this is not so, this homoeroticism was already talked about in the 90s, but now we have ignored it,” says the curator and adds that “Picasso’s artistic relationship with gays were not anecdotal, they were almost a category, at least in that period. Then they disappeared with Cubism, but reappeared in the 20s and 30s. For me, Ladies of Avignon represents a return to order.”

And he goes on to assert that “these images begin in the Blue Period,” and explains that in many of his paintings, “he turned the body into a site of linguistic and cultural experimentation, to which he brought sensuality,” and adds that this “also opened doors to the performative presence of gender. Picasso knew what otherness was and lived it very actively. The first person to say that Picasso’s harlequins are neither men nor women, but something else, was Apollinaire.”

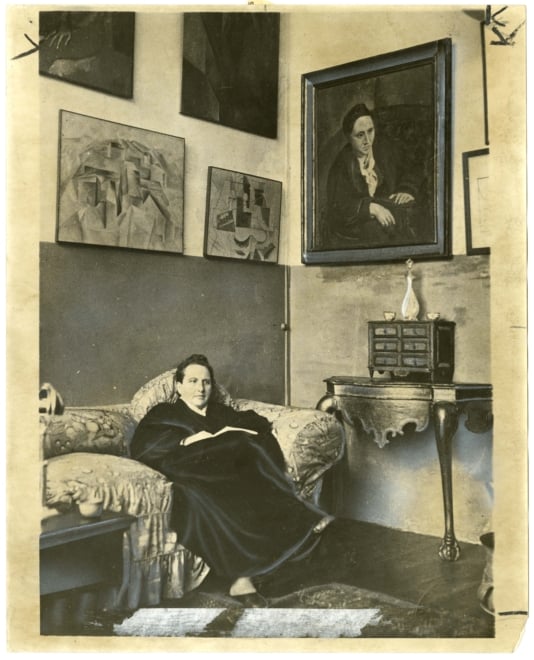

Gertrude Stein sits on a sofa in her Paris home with a portrait painted by Picasso. At the top right is a detail of his office, and at the bottom is his portrait in contrast to Picasso’s self-portrait in the Reina Sofia exhibition.

For this reason, the body occupies most of the eight sections that make up this exhibition, in which Stein is the protagonist in one of them, and Fernande Olvier in another. “The fifth part of the exhibition is devoted to the iconic type of female nude that Picasso developed in 1906 and which critics identified with Fernanda, his companion from August 1904 to 1912, and whom he also depicts as a peasant woman in his stories. to Gosol, where he spent the summer of the same year. A place that also plays a leading role in the exhibition, since it is there that “away from friends, but supporting them with writing, the artist adds the folk component of this place, including the inhabitants of the Pyrenean village, radiating calm.”

There is another part of the exhibition where an attempt is made to shed light on the significance that primitive art had in the evolution of Picasso, in his work. The Malaga man studied Egyptian, Iberian and proto-historic Mediterranean art… “His influence can be seen in e.g. Bust of a young womanwhose face is mysterious and where the artist resorts to the appropriation of Egyptian and Etruscan art,” explains the institution and adds that “the treatment is deliberately rude and not final It has been replaced by writing that gives the impression of incompleteness. All this takes him to a new period, to the search for a different artistic experience.” As Segade says of the exhibition, “it’s a journey through the visual culture of the early 20th century.” Picasso is forgotten rather than unknown.

Source: El Independiente