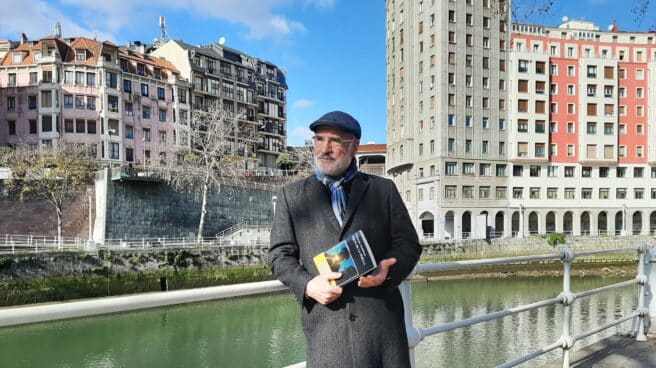

Basque writer Fernando Aramburu next to the Ria de Bilbao during the presentation of “Hijos de la fábula”.

The announcement was expected for several days. The question that swept through the whole country was what scale it would have. The group’s “historical” claims have been repeated too many times, almost always disappointing the public to not be viewed with skepticism. That Thursday, however, the optimists prevailed. On October 20, 2011, ETA announced a permanent end to its attacks, kidnappings and threats. The structure of the terrorist organization has been bleeding for years due to arrests. The inclusion of new fighters became increasingly sparse and less experienced. Almost always younger and with ideological support, full of memorized slogans.

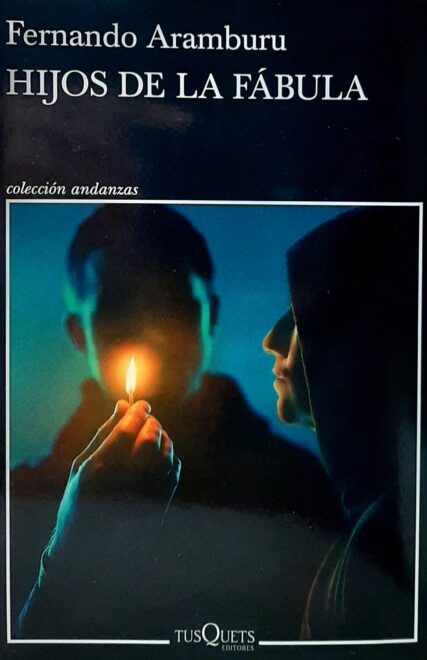

This image was also seen on television by Fernando Aramburu (San Sebastian, 1959). He is one of the writers who best described the impact of the violence that ended that autumn day. Your ability to describe it will haunt you. He realizes that “Patria” will be a shadow that will always accompany him, especially if he writes about ETA. For several days now, he has been presenting his latest work, Hijos de la fábula (Editorial TusQuets). In it, he talks about the impact of the story, the “fable” and its ending. A fiction that has forced many young people to cross the “red line” of weapons and the end of which left them trapped: many in prison, others dead, and the main characters of his latest work in a sarcastic limbo.

IN ‘Sons of the Fable’ Aramburu uses humor to recreate the nonsense of terrorism. The story was born in his head almost simultaneously with the appearance of “Patria”. Since then, he has been sleeping in a drawer, waiting for his place, his time, and his proper context. In 2011, a story like that of Asier and Joséba, two young people who travel to France to join a group just as it announces its end, can be misunderstood. Today, the passage of time allows us to understand, look back and laugh at a grotesque story in which, in many cases, barbarism is hidden.

History speaks for itself. Two young would-be heroes, idealistic, without money, without experience, without weapons, without social support, waiting for instructions, hiding in a chicken farm in the south of France. The rules of a group that no longer exists. Both will decide to declare themselves the ideologists and strategists of their own struggle to save the Basque homeland. “I remember when I witnessed the announcement of the cessation of armed activities, I wondered what would happen if someone from ETA did not agree and took up arms to continue on their own. It’s simple, just take a simple gun and do the action. It would be enough to reject this statement. This is how I imagined “Hijos de la fábula,” says Aramburu. A story in which humor is one of the storytelling mechanisms.

Question. – Did writing a story about two ETA terrorists with humor make you doubt how far you could go?

Answer. – I decided to leave the victims of terrorism out of history. It gave me leeway to approach it with a certain type of humor that is not comedic but satirical humor that tries to delegitimize the use of violence.

IN.- Eleven years have passed since the announcement of the demise of ETA. Is society ready to laugh at ETA?

R.- I am not the first to ridicule the aggressor or against him. There is historical precedent for some tyrants to laugh and parody. I was connected, and I liked it, with Chaplin’s The Great Dictator. There are no Jews or Auschwitz in your film. If victims appear, we risk increasing their suffering, and this cannot be, I would never cross this red line.

Aramburu admits that before publishing the novel, he asked the opinion of a victim of terrorism. He did this by assuring him that the victims would not appear in “Hijos de la fábula”. “So I overcame my doubts about being able to hurt people who had already suffered a lot.” He identifies with a phrase that the philosopher Fernando Savater heard a few days ago when he stated that those who fought ETA in a civilian way “wanted to ‘outlive the terrorists and then laugh at them’, I think that defines my goal well.” “.

This work, like Patria, is not really a novel about ETA, but rather about the impact that the group had on society, on people, on their neighbors: “I am not interested in ETA, but on the people of my land and as ordinary neighbors influenced by our collective history. This is the raw material for my stories that run through the Basque Country.”

“Basque people”

“Hijos de la fábula” is the third work that brings together a series that Aramburu called “Basque People”, and which completes “Los peces de la amargura” and “Años lentos”, works in which ETA is somehow present. “Patria” does not appear in the series, “it is too big and will overshadow all the others,” he notes.

IN.- He chooses two gullible terrorists who are not doing well and whose actions end up making the reader laugh. Because?

R.- In fact, the narrator does not describe Asier and Joseph, it is their actions, their words and discussions that lead the reader to conclusions about what they are. I would say that they are fools, but not stupid. There are even “Basque” reflections in them, not devoid of a certain content. I made sure it wasn’t just two kids who want to join ETA, but I gave them a family background, friendship, women, suffering, love, eroticism… I gave them a certain human dimension.

IN.- Are the terrorists you describe in some way victims of what ETA has instigated?

R.- Yes, I think they are victims, obviously not of the same level and not of the same nature as the victims of terrorism. Some kids who could have a normal family life, job, etc. who get into it, get into propaganda and then get killed or arrested to spend 20 or 25 years in jail… that’s not a model life, no.

IN.- Many young people today do not perceive ETA and its impact in the same way as those who have suffered from it. In some cases, some mysticism even spread throughout that world, even praising these figures. You understand?

R.- I have worked with teenagers a lot and I know that they only pay attention to the present, and not to the history of their parents or grandparents. There is a hegemonic discourse that effectively blurs the truth. In addition, the landscape these young people find themselves in is quite acceptable, no burning buses, no violent demonstrations… They are not going to reflect on a reality that they have not experienced. That’s why it’s very likely that many of the comfort considerations accept speech that is a bit bleaching.

IN.- And against it…

R.- I have insisted many times that memory should be developed, but not in the human brain, which is very fragile. Witnesses die, and the brain deteriorates, so I find it very pedagogically useful to create testimonies, to create a memory bank in the form of films, photographs, novels, historiographical books, etc. A memory bank, in which today’s kids, if they are curious and interested, can go in search of the most truthful information.

Aramburu knows that in Euskadi the novel will be perceived differently. The suspicion with which Basque nationalism received Patria hopes that it will not be repeated on this occasion, although it does not rule it out: “There will inevitably be a political reading in Euskadi, but this does not seem bad to me. Seems like an easy read to me. The policy is set by the one who reads, not by the book.” He also believes that the Basque reader, in contrast to other areas, “perhaps is able to read between the lines and understand many allusions, to feel a certain familiarity with the language modes of the characters.

A work in which the author has set himself a special linguistic task and which he defines as “artisanal”: “There is not a single sentence in the whole book with more than one verb. I think the manner of speech of two young men from Gipuzkoa suits them very well. This led me to invent other resources such as fillers typical of the earth so that the text is not a sequence of telegrams. The next step has not yet been decided. Aramburu, “with m before b, like my father and my grandfather,” claims to have drafts of unpublished works in his desk drawer. At the moment, neither the topic nor the genre is closed, but a hint is put forward: “I haven’t suggested stories for a long time and I will say that now this is what is in priority.” But even then it will be Fernando Aramburu “the one from Patria”: “I even joked with my editor that they would not put my name on the cover, but simply “the one from Motherland’“.

Source: El Independiente