Honey producer from Yemen, one of the countries most affected by famine in the world.

In the poorest half of the world, investing public resources in agricultural R&D can yield impressive benefits at very modest costs. As we have explained in this chapter, innovation has played a very prominent role in increasing food production and reducing world hunger. Indeed, a scientific article confirms that R&D investments lead to improved food production efficiencywhich leads to lower prices and at the same time a reduction in the number of undernourished people.

However, in the poorest half of the world, investment in agricultural R&D has lagged by more than a century. Almost all agricultural R&D funding comes from rich countries.

Almost all agricultural R&D funding comes from rich countries.

The main reason is that large farms in rich countries, whose property rights are guaranteed by law, can afford the costs of purchasing very expensive but profitable technologies, such as new varieties of seeds. They have wide access to scientific knowledge, funding and agricultural infrastructure to implement any innovation. While farmers in low- and lower-middle-income countries have access to only a small portion of these resources.

Consequently, poor countries receive a very small percentage of global investment in agricultural technology. In 2015, 80 percent of agricultural R&D funding went to high- and upper-middle-income countries, while lower-middle-income countries received almost all of the remaining 20 percent. There have been virtually no resources allocated to agriculture in the world’s poorest countries.

This is one reason why the first Green Revolution was much less beneficial for poor countries than for others.With. In contrast, technological innovation, along with fertilizers and irrigation, has helped the developed world much more. From 1961 to 2021, grain harvests in high-income countries tripled, while low-income countries saw a much more modest increase of just 60 percent. The problem is not that poor countries cannot produce more food, but that they lack the necessary technological investment to do so.

If governments direct investment in innovation towards poorer countries, this step could make a significant difference. The agricultural economists I’ve worked with believe that R&D is the intervention that, on its own, can produce the greatest benefit per dollar spent.

The main reason is that one technological innovation can help millions of farmers with great impact. For example, finding high-yielding seeds improves agricultural production wherever that plant can grow well. Moreover, innovation also pays off when other parts of the system do not work as well: even if the coverage of irrigation or mechanization is very limited, planting better seeds always means higher yields.

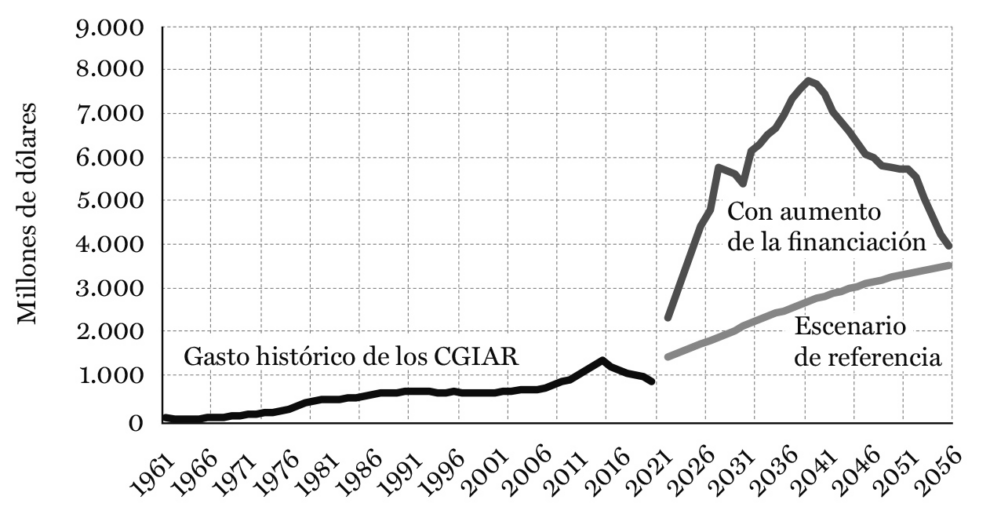

To help the Global South, additional R&D investments shown in Fig. 7.9 next to their historical evolution, should be directed in four different directions. First, to improve food security, poverty and ecosystem services worldwide, money will need to be allocated to international centers to advance research, technology and legislation; For practical purposes, this would mean continuing the first Green Revolution on an international scale. These centers already exist and are known by the acronym CGIAR.

Second, the scientific article requires that investment come from national agricultural research organizations. This point is vital because these organizations usually conduct very important research at the local level to improve agricultural efficiency in specific countries. Without their participation, it will be very difficult to find solutions adapted to the climate and local context.

Innovation also pays off when other parts of the system fail.

The third investment will be smaller and will be aimed at innovations that will increase the efficiency of the first two areas. For example, obtaining plant DNA sequencing is much faster and less expensive. Fourth, to expand the choices available to consumers in developing countries, investment should be directed to the private sector.

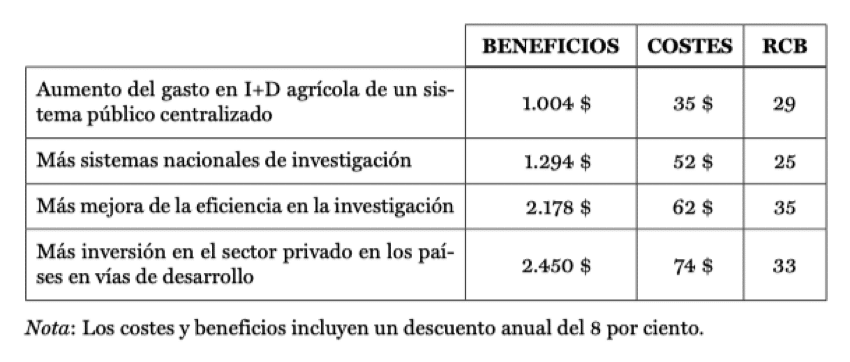

As we summarize in Table 7.1, the authors use the model to calculate the impact of investments in these four different areas INFLUENCE. This model has been proven time and again to be reliable and can produce physical results (such as increased yields), economic benefits for producers (such as increased farm income), and consumer impacts (such as falling food prices and malnutrition). rate) and other general consequences (for example, GDP growth). The calculated benefits correspond to the increased income of farmers, who could produce more, and the benefits that would accrue to consumers because they would pay less.

Of course, each time one of these four funding streams is added, the overall cost of the package increases, but so do the benefits. These incentives will help farmers, who will be able to produce more food and therefore receive a higher overall income, and will also help consumers, who will be able to buy more food at a lower price.

Table 7.1. Costs and benefits in billions of dollars and cost-benefit ratios of increased agricultural R&D, 2023–2056.

With a 30 percent increase in private sector investment in developing countries, the entire package would be worth $74 billion over thirty-five years. This figure is equivalent to an annual increase of $5.5 billion.

However, these investments could generate a total benefit of US$2.45 trillion; an impressive return of $33 for every dollar invested. As we show in Table 3.1, this would equate to $184 billion in benefits per year.

By 2056, relative to maintaining current levels of funding, this additional investment in R&D in developing countries would increase agricultural production by 10 percent and reduce food prices by 15 percent.

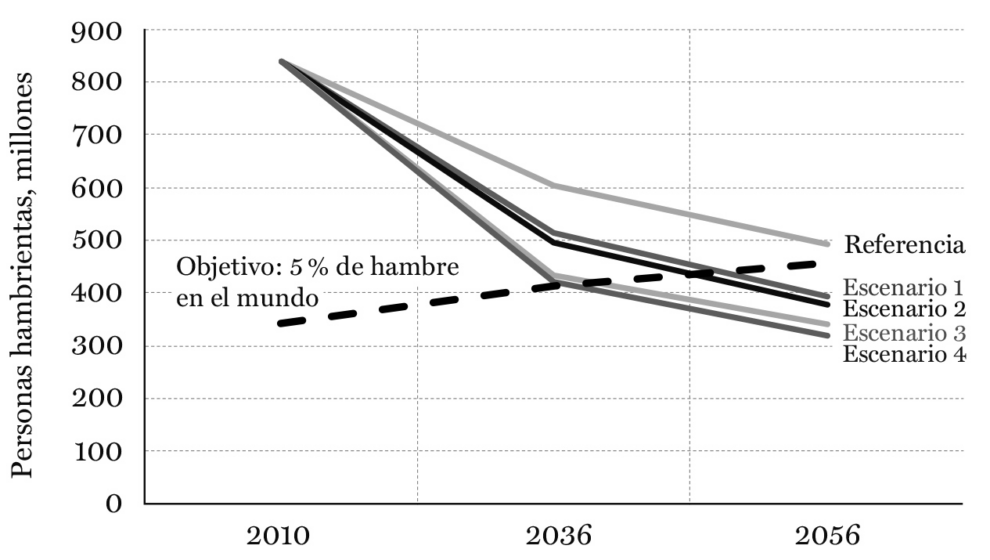

In addition, this measure will allow many people to obtain the food they need to live. As Figure 7.10 shows, each new financing channel further reduces the level of malnutrition. The full package will bring us closer to achieving the new SDG target of reducing hunger to 5 percent by 2030 and open the door to further reductions by mid-century.

This additional R&D is also likely to increase GDP, but out of academic caution this factor was not included in the benefits calculated in Table 7.1.

It is estimated that the entire package could increase developing countries’ GDP by about $2.2 trillion in 2036 and $13.7 trillion in 2056; that is, an increase in per capita income of 2 and 6 percent, respectively. If the cost-benefit ratio is calculated based on this increase in GDP, then the RBI of each package will be eight times higher; a fact that surprises.

Additionally, through increased efficiency, this additional research and development will reduce global emissions by more than 1 percent.

The ability to (virtually) eradicate hunger

When it comes to agricultural research and development, world leaders have policies at their disposal that can make a difference. An additional $74 billion in investment would improve farmer and consumer welfare by $2.5 trillion and lift 130 million people out of malnutrition by 2030.

With just a small increase in investment, and spreading the benefits of the Green Revolution over the coming decades, world leaders could save more than 100 million people from hunger.

This policy is also much cheaper than experts predict. The FAO has estimated that living in a world in which only 5 percent of people suffer from hunger will require an investment of $340 billion annually between 2016 and 2030, a total equivalent to $5 trillion (FAO 2015, 11). Additionally, to increase GDP to a level that ensures that less than 5 percent of the population suffers from hunger, FAO recommends an additional $1.9 trillion in investment annually, most of it in non-agricultural sectors (FAO 2015, 21-27). . We’d all like to be able to do something like this, just as we want fewer recessions and more economic growth, but it’s hard to imagine spending $28 trillion to fund this FAO measure.

In contrast, agricultural R&D funding is on the verge of reaching the same 5 percent target, with only $74 billion in additional investment. And it can generate much more economic growth per dollar spent. In doing so, the investment will not only make farm workers more productive, but will also enable many more people to be productive and innovative in other sectors. There would be more food, lower prices and fewer people going hungry.

This policy applies the same miracle formula of innovation and growth that has allowed most of humanity to avoid starvation. With just a small increase in investment and spreading the benefits of the Green Revolution over the coming decades, world leaders could save more than a hundred million people from hunger.

Extract from What works: 12 most effective solutions to eradicate poverty and achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goalspublished by Deusto.

Bjorn Lomborg is a Danish academic, writer and environmental activist. He is president of the Copenhagen Consensus Center, a think tank that brings together the world’s best economists, including seven Nobel laureates, to research, identify and promote the most effective solutions to major global problems. in Political Science from the University of Copenhagen, he was a visiting professor at the Copenhagen Business School. He is also the bestselling author of The Skeptical Ecologist (Espasa, 2003) and False Alarm (Antony Bosch, 2021).

Source: El Independiente