Two children walk down the street during the Covid pandemic.

From April 5 to May 26, 650 probable cases of new acute childhood hepatitis have been identified in 33 countries. This is the latest data from the World Health Organization (WHO). The country with the most cases is by far the UK (222 cases, 34%), while Spain’s latest health report includes 30 cases through May 27.

New childhood hepatitis hit the media on April 5 after the UK reported a dozen cases to the WHO. Children under the age of 10 suffered from symptoms such as jaundice, diarrhea, vomiting and abdominal pain that were severe and required hospitalization.

The European Center for Disease Control (ECDC) sent out an alert on April 12, and the first cases of hepatitis in children were reported in Spain before the 19th of the same month. The first three cases were in Madrid and since then the number of new cases has been increasing around the world. The severity of the disease varies, but the percentage of children in need of a transplant is about 5%, and the WHO has reported nine deaths. In Spain, there has not been a single liver transplant to date, and only one.

There were many unknowns from the very beginning, and only a few have cleared up at the moment. The analyzes revealed the presence of a significant percentage of adenoviruses in affected children, which gave rise to the adenovirus hypothesis: the end of the pandemic would lead to a greater current presence of these viruses, which was not the case in young children. exposed earlier.

A few weeks later, the etiology “remains unknown and under investigation,” as the WHO stated in its latest report, where it also warns that “cases are clinically more serious and a higher proportion of patients develop acute liver failure compared to previous reports. The organization maintains a “moderate risk” for this new disease.

Despite the remaining doubts, SARS-CoV2 intervention has entered the hypotheses with greater force. “One adenovirus does not appear to be the cause, it is hypothesized that it could be a cofactor, and one hypothesis is that it could be Covid, although Covid was not found in all cases,” explains Maria Buti, a hepatologist from Hospital Val d’Hebron de Barcelona and former president of the Spanish Association for the Study of the Liver. “Covid will exacerbate the course of the disease,” he adds.

The role of Covid in new childhood hepatitis has also been put forward as a possible hypothesis in a recent article in Lancet, where the “superantigen” theory was launched, which could be behind these hepatitis. The mechanism was explained by CSIC researcher Matilda Canelles in an article in Talk. Canelles explains that there is a sequence in the spike protein of SARS-CoV2 that resembles another one found in the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus, and that it is called enterotoxin B. This sequence is called a “superantigen” because the immune system perceives it as an antigen. great danger and provokes against it “a rapid and powerful inflammatory reaction”. Canelles emphasizes that “it is believed that a recent mutation that appeared in Europe may enhance the similarity.”

In addition, the researcher emphasizes that in mice, adenovirus infection can cause hypersensitivity to enterotoxin B. “With that, we would already have all the pieces of the puzzle,” says Canelles. “SARS-CoV2 infection with viral accumulation in the intestine [los niños acumulan más virus en el tracto gastrointestinal que los adultos] and the entry of viral proteins into the blood due to increased intestinal permeability; adenovirus infection, which can sensitize the immune system and cause an overreaction with subsequent inflammation of the liver.”

However, this remains a hypothesis, as Booty recalls: “The etiology remains unknown, and the fact that adenovirus or Covid was found does not mean that they are ultimately to blame.”

Several hypotheses are being considered and seven are cited in the latest Department of Health report regarding cases in the United Kingdom:

- Abnormal host (child) susceptibility to or response to adenovirus, which may lead to more frequent progression of adenovirus to hepatitis due to:

a. No impact during the COVID-19 pandemic

b. Effect of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (including Omicron variant) or other infection.

in. Co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 or another infection.

d. Toxins, drugs, or environmental exposure. - An increased incidence of common adenovirus infections highlighting a very rare or unrecognized complication.

- New adenovirus variant with or without cofactor addition

- Post-infection syndrome SARS-CoV-2 (including limited effect of Omicron).

- Drug, toxin, or environmental exposure.

- A new pathogen acting alone or as a co-infection.

- New variant of SARS-CoV-2

Pediatricians continue to monitor cases with “great concern,” says Booty, especially focusing on cases in which the disease is fulminant and requires, for example, a liver transplant.

However, the hepatologist is optimistic about the progress of the disease in our country: “The curve that was in the United Kingdom does not appear in Spain, where it does not look like there will be such an increase in cases. The difference with these countries could lie in some environmental or genetic factor, but it has not yet been identified.

Cases of childhood hepatitis in Spain

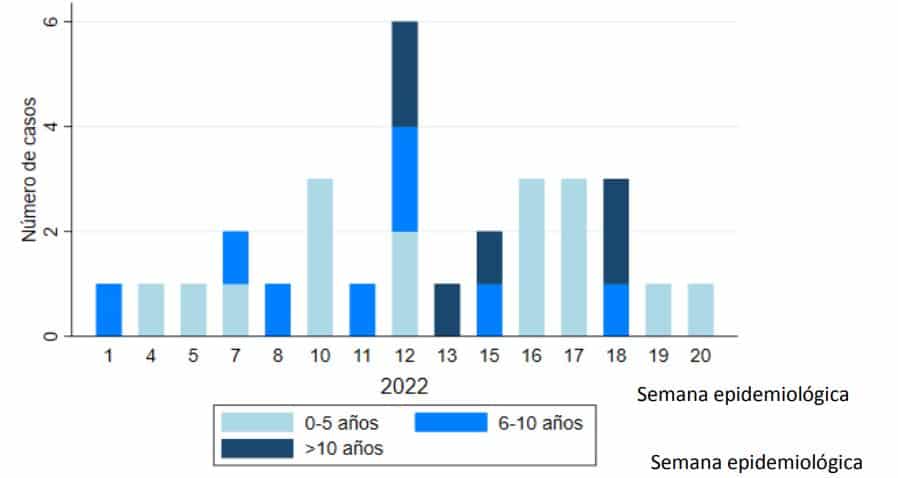

The truth is that in Spain, new cases have slowed somewhat in recent weeks after peaking in week 12 (March 21-27).

Epidemic curve of cases of severe hepatitis of unknown etiology by age groups and epidemiological weeks of onset of symptoms.

Madrid is the autonomous community with the highest number of cases, 11, followed by Galicia (5), Catalonia (4), Balearic Islands (3) and Andalusia (2). Aragon, Canary Islands, Castile y León, Castile-La Mancha and Murcia each registered one case until 27 May.

The median age was 6.1 years, and by gender, 63.3% of cases were girls and 36.7% boys. As of May 27, 20 people have been discharged from hospitals, four remain in the hospital (no information on six). One child required a liver transplant.

The most common symptoms of childhood hepatitis were vomiting in 63%, fever in 59%, jaundice in 52%, vomiting in 32%, and respiratory symptoms in 21%. Skin rash was also reported in eight cases (30%).

Microbiological analysis “does not indicate a clear viral etiology, although, like the results provided by other countries, adenoviruses and adeno-associated viruses are often detected,” the Ministry of Health indicates in its report. Only nine of the 27 cases analyzed were positive for adenovirus, and two of the 24 analyzed developed SARS-CoV2. In four more cases (out of nine analyzed), antibodies were detected. Only eight of the 28 analyzed received the Covid vaccine.

Source: El Independiente